- Nomination for the “Research through Architecture / Architecture Books” section

The mediterranean architecture in romanian interwar period

Authors’ Comment

The present work responds to the need to study the Mediterranean Style, a moment completely forgotten and neglected for more than 90 years.

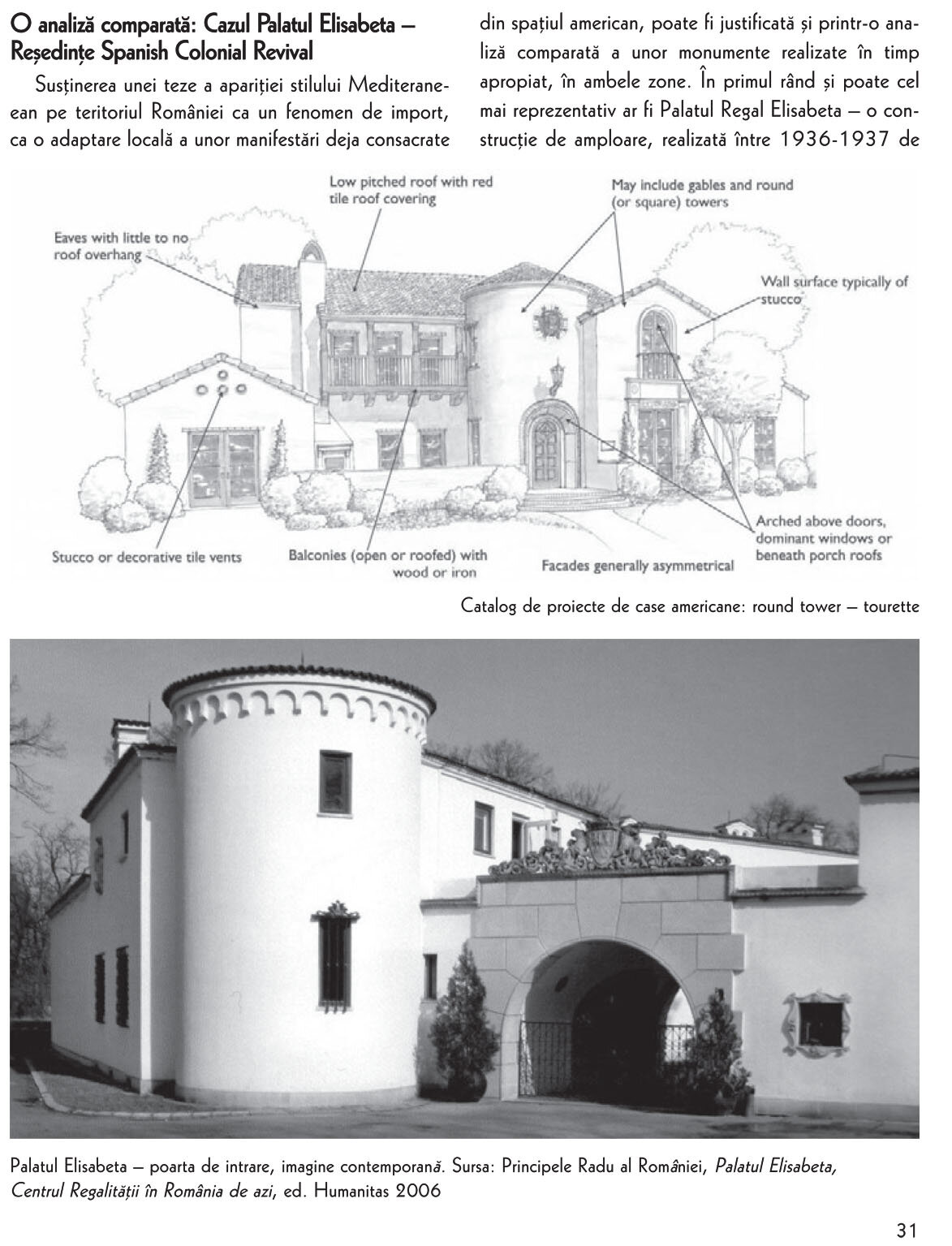

Benefiting from a name that varies from the simple Mediterranean, Mudejar, to Florentine and Moorish-Mediterranean, to the hallucinatory Mauro-Brancoven, in a real concert of ideological confusions, the terminology has not yet acquired its ultimate identity, although the eclectic character- historicist and borrowing from the American and Iberian space of the phenomenon is quite obvious.

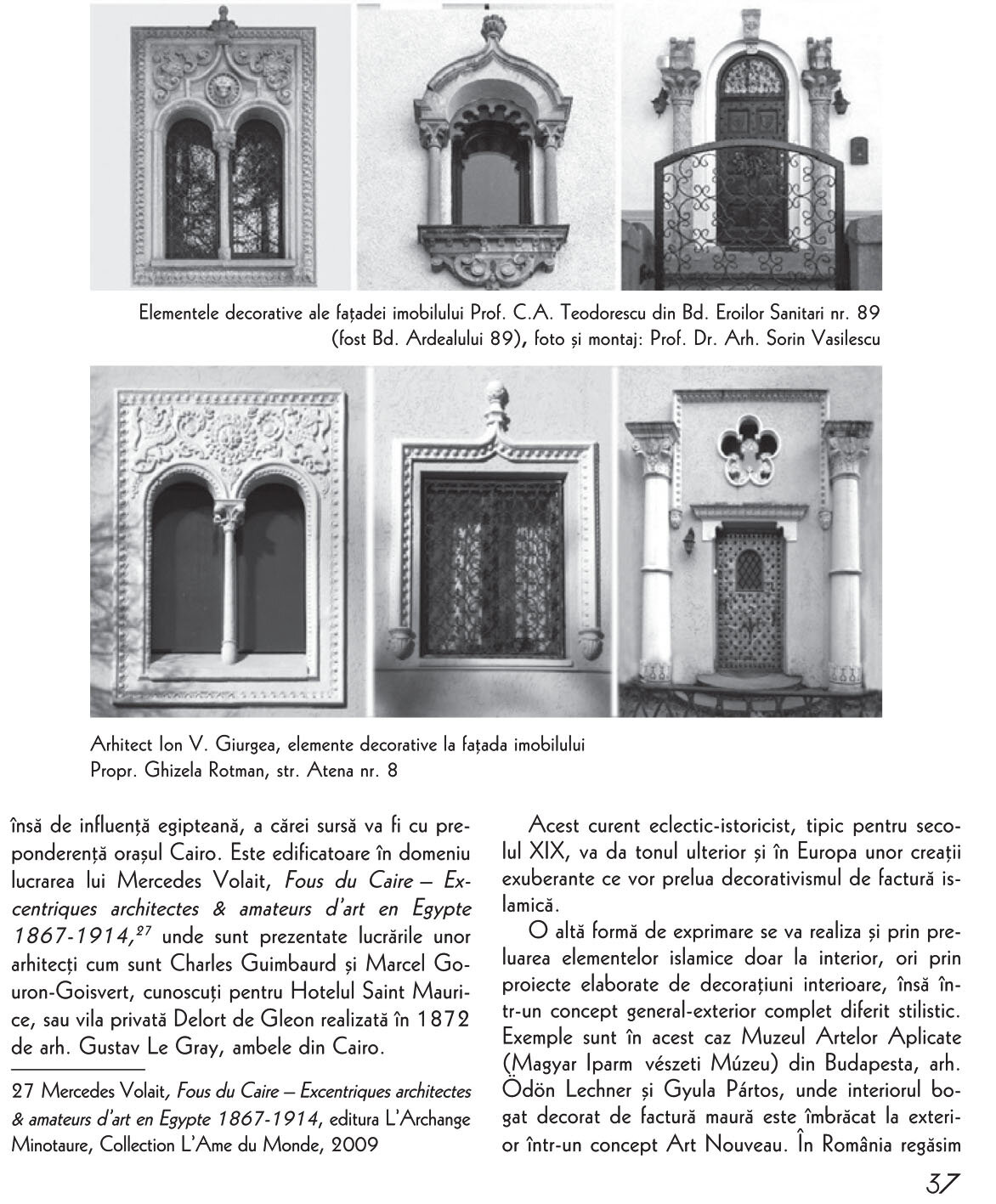

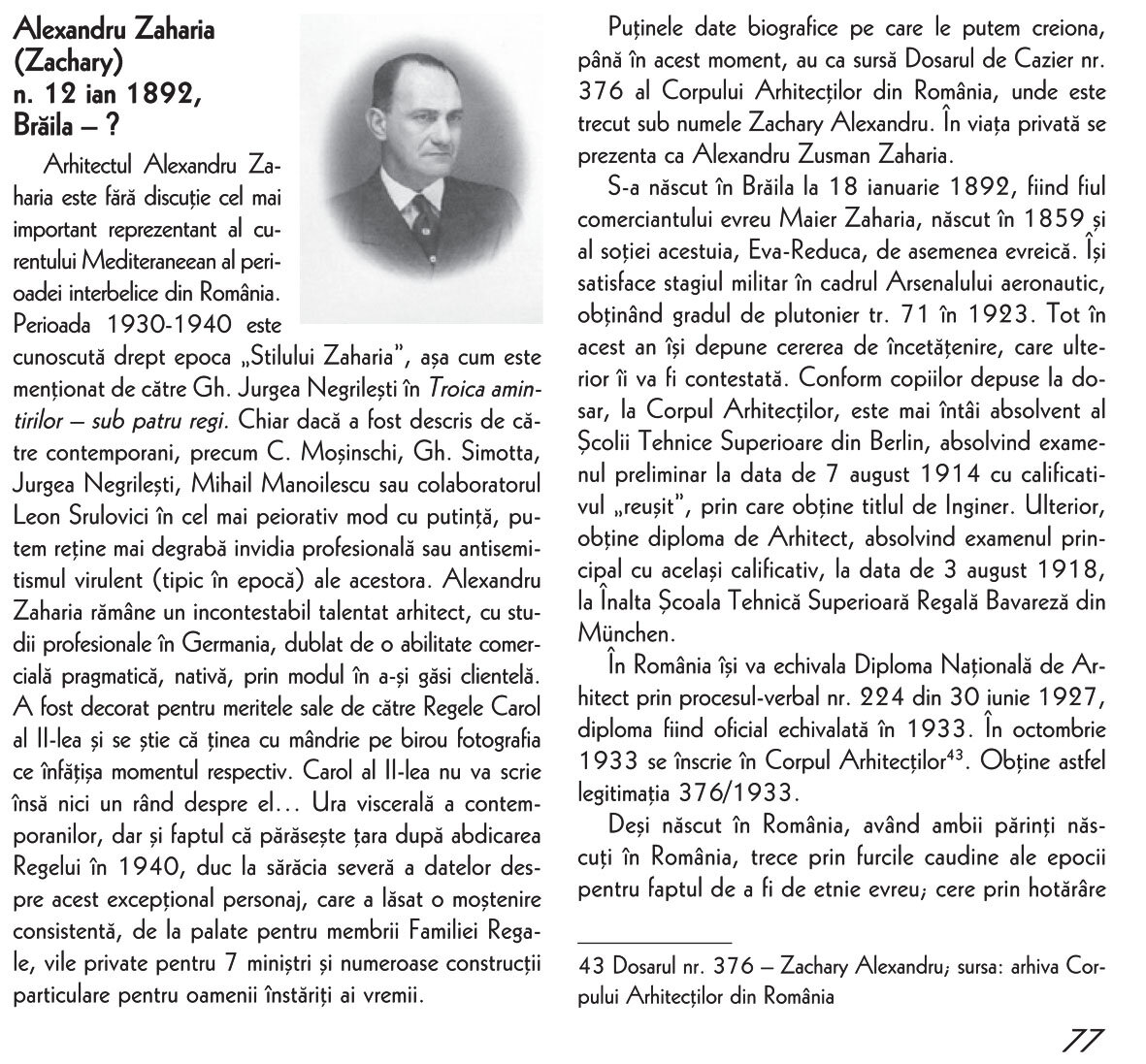

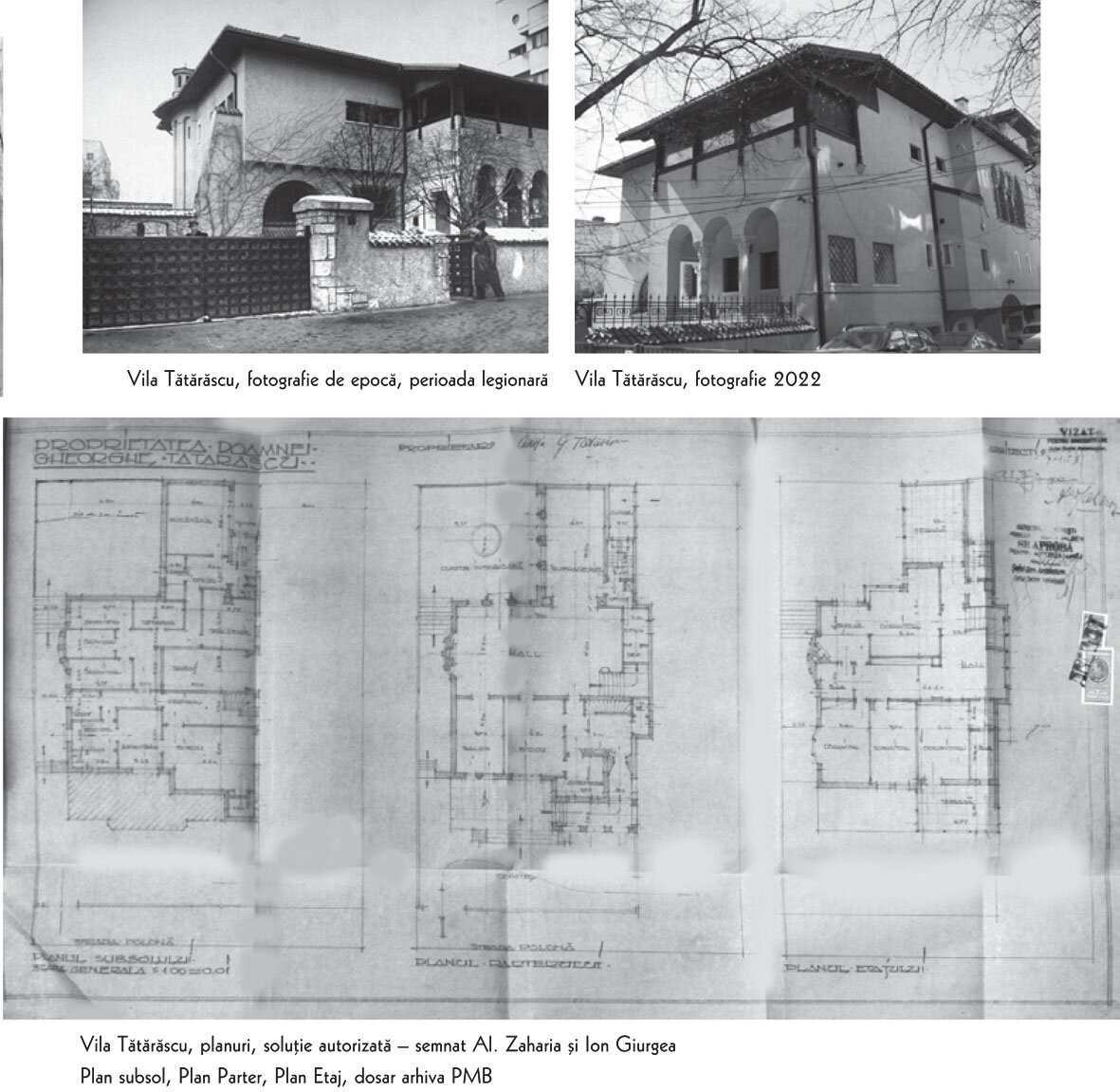

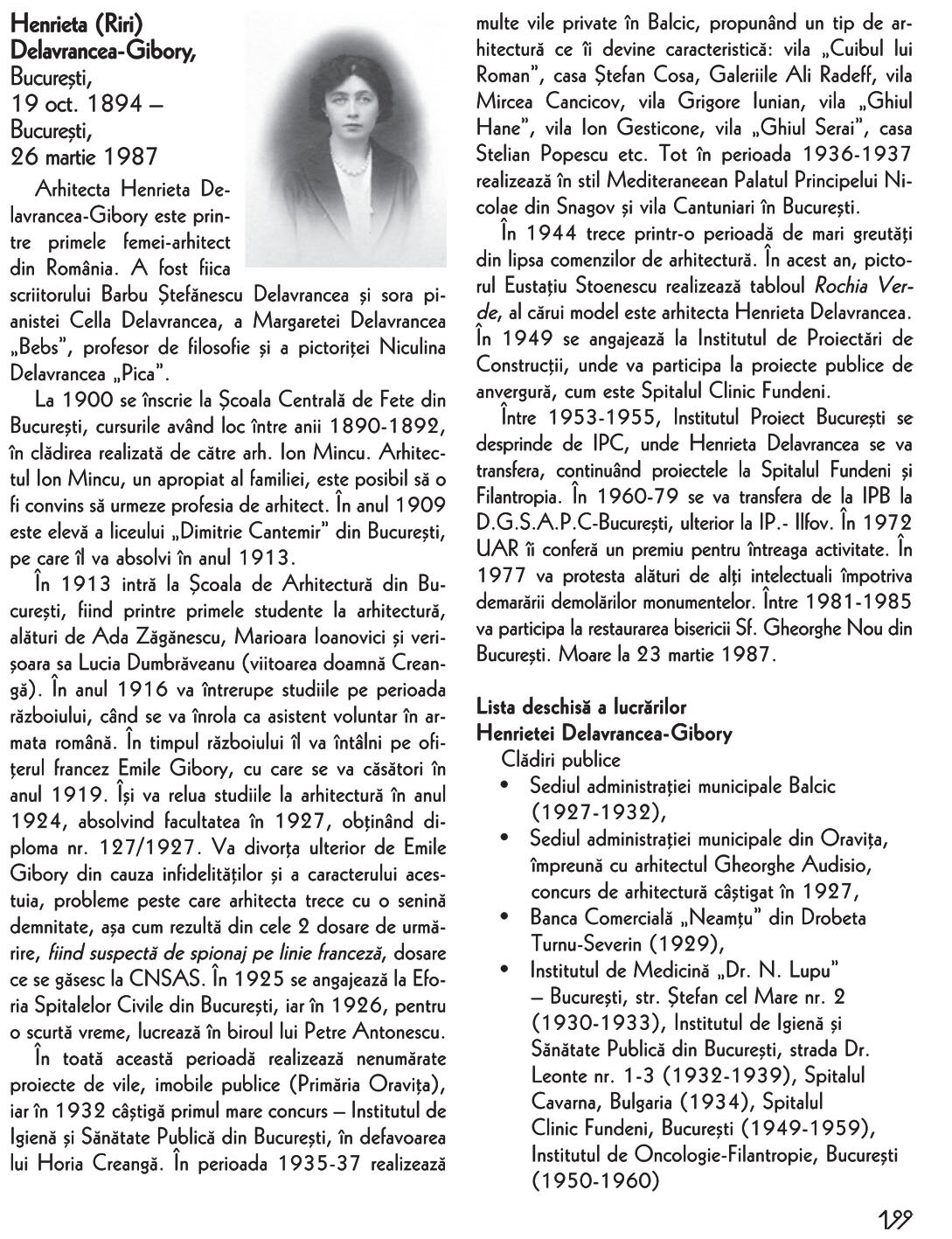

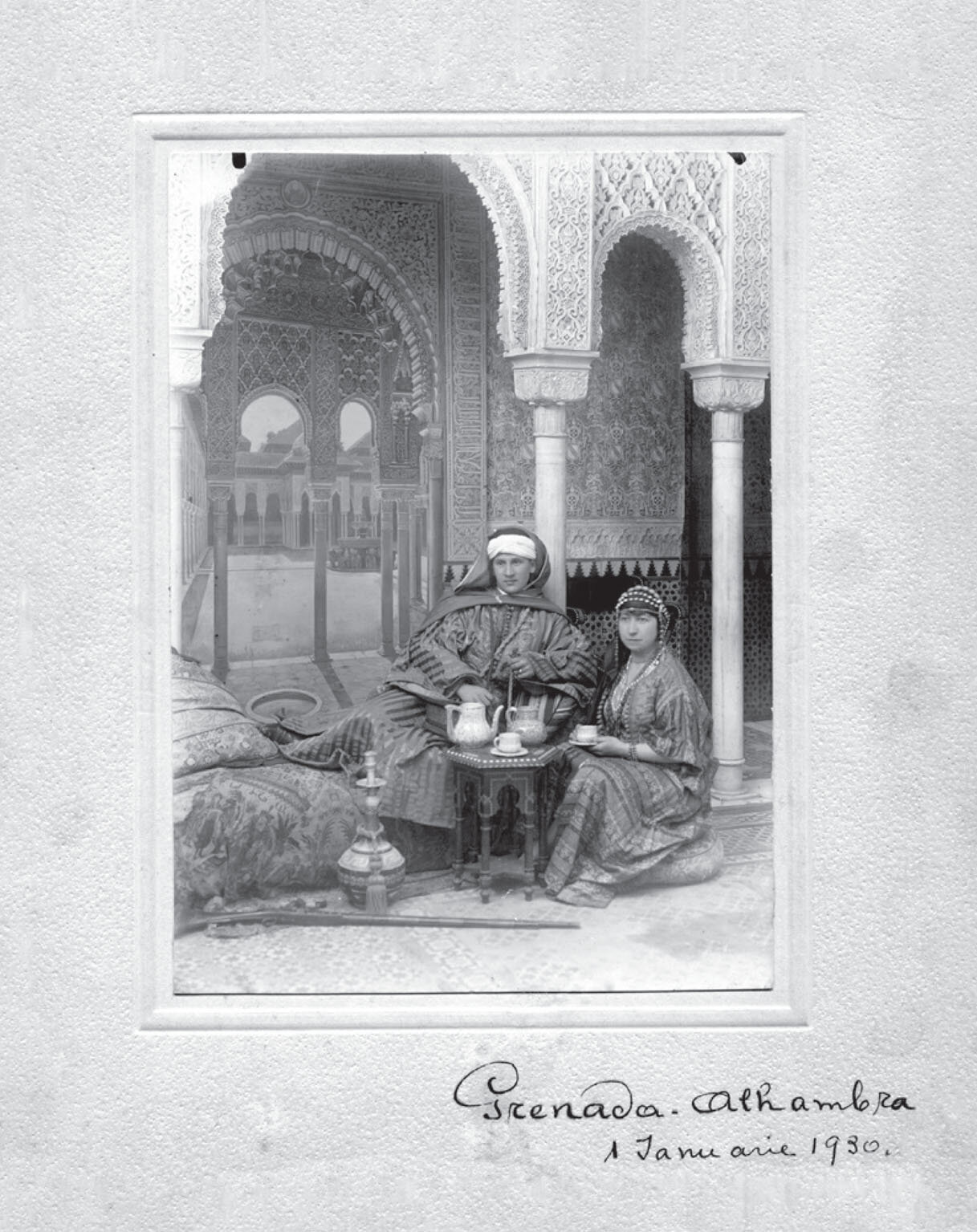

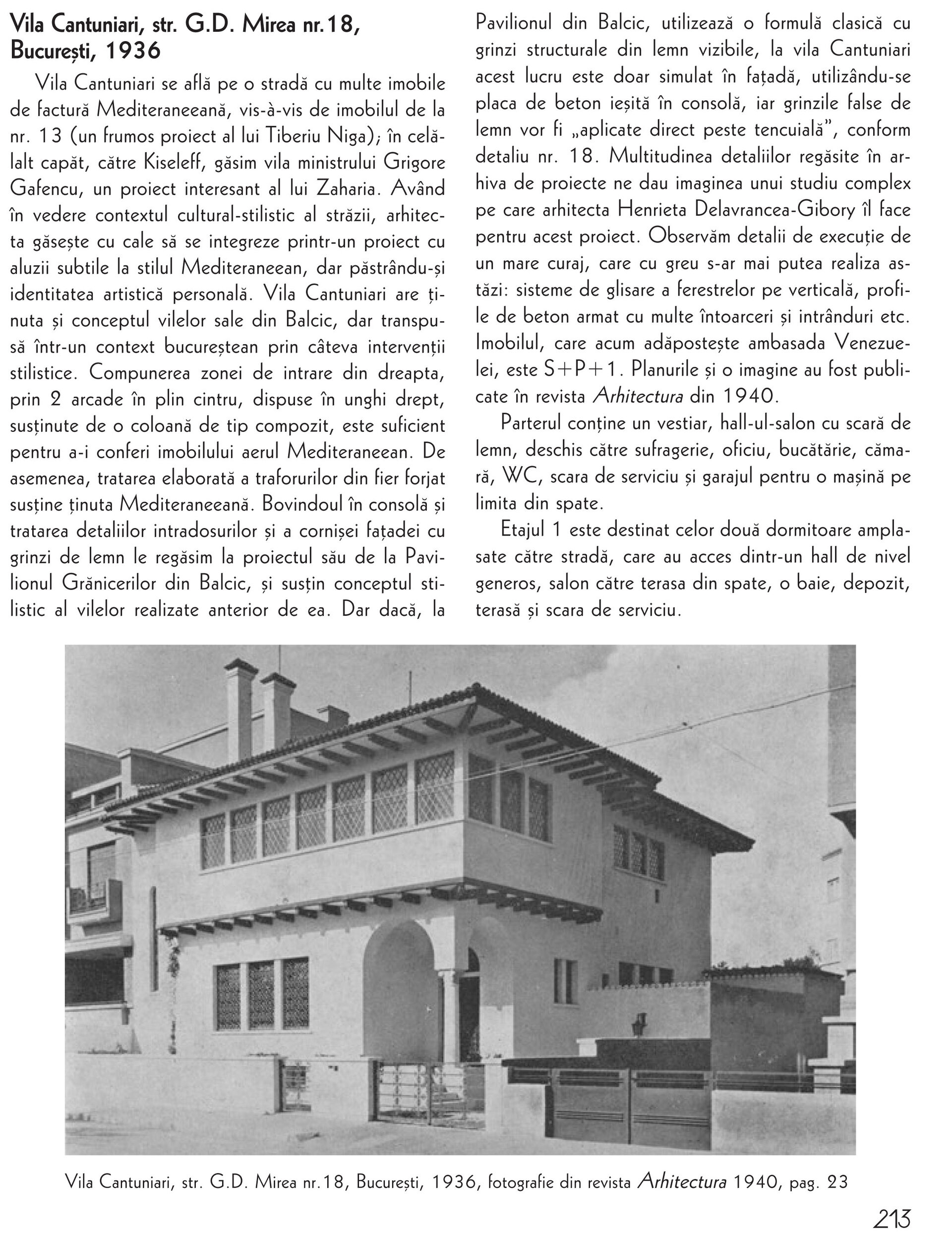

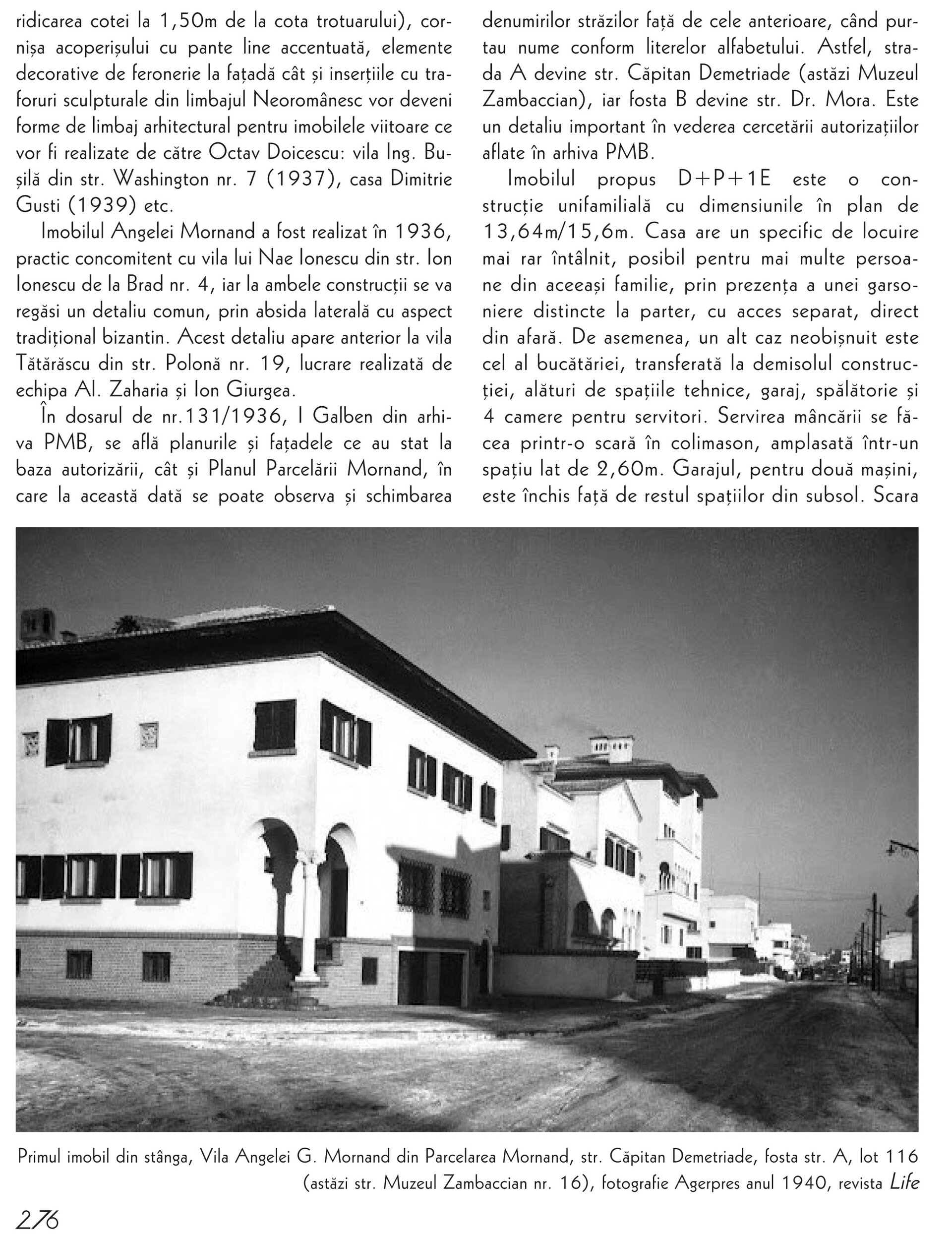

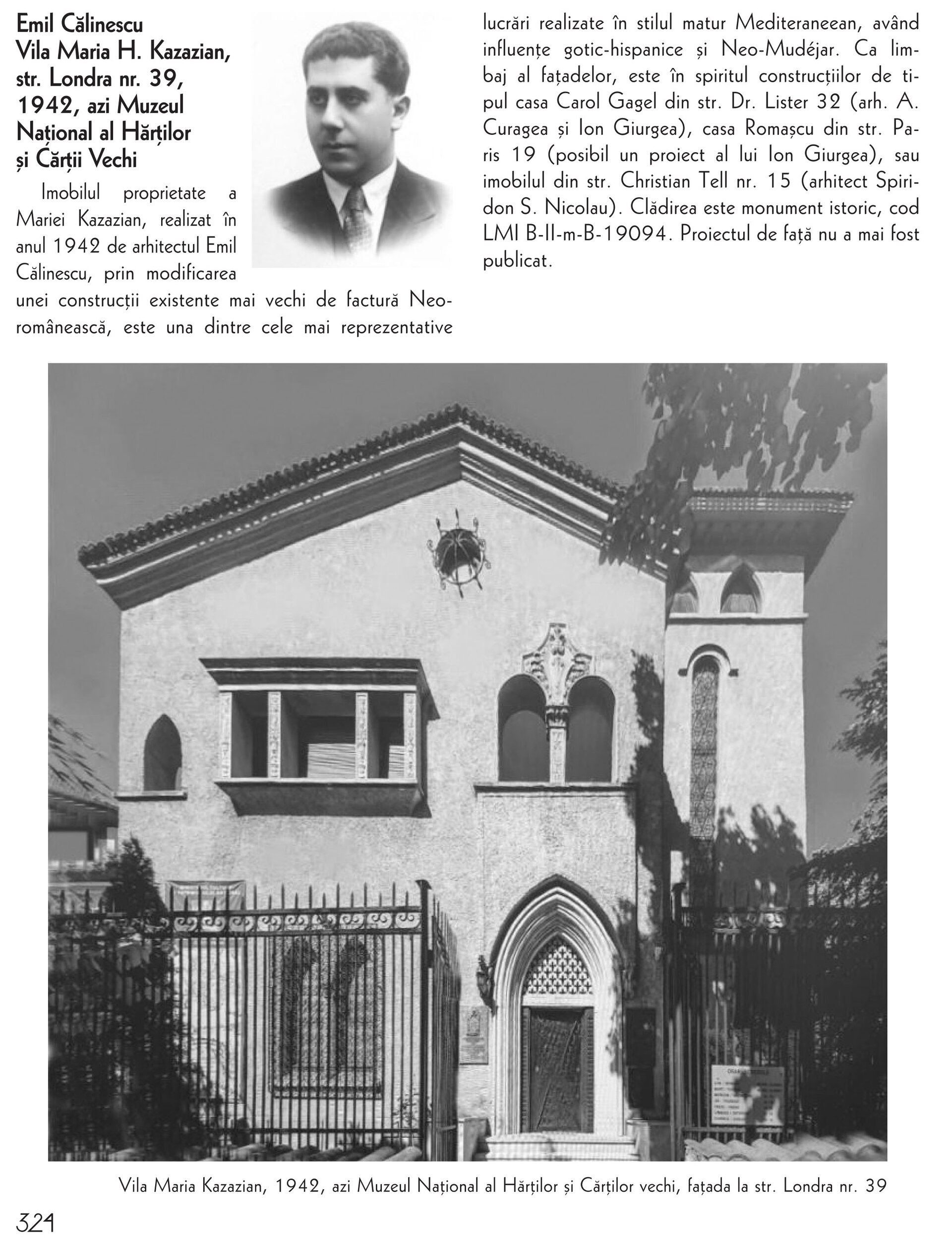

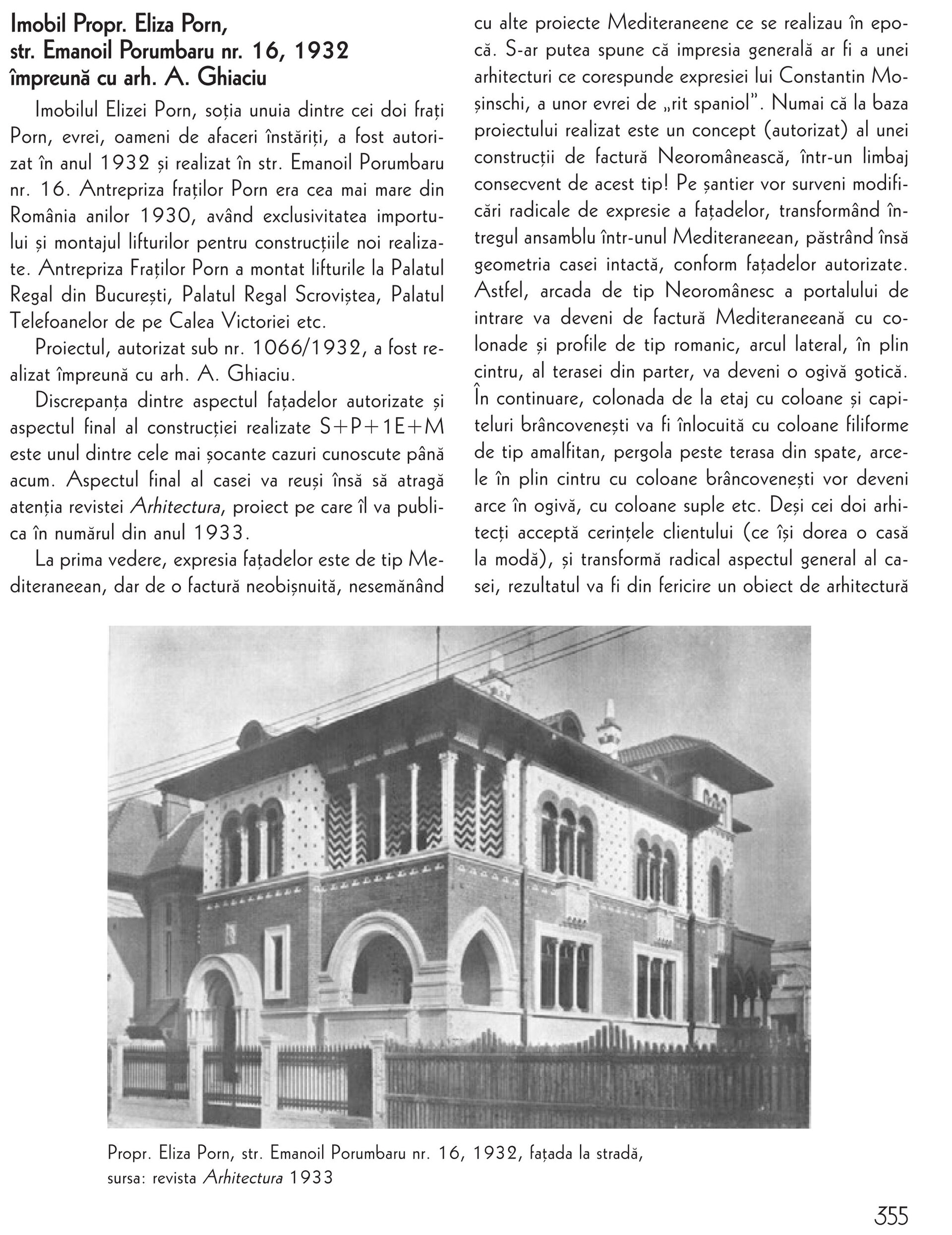

Is it a phenomenon that belongs exclusively to the cultural space of the European Mediterranean, as it is apparently called? We can say that traveling in the spirituality of Mediterranean architecture, which manifested itself in a specific way in the first half of the century. XX, also meant meeting the complex and varied world of the two Americas, the luxurious villas of Santa Barbara, Hollywood and California, the opulently decorated residences of Florida, the cultural influences of Hispanic Mexico, but also the Moorish influences of the Alhambra, Cordoba and North Africa. Many Romanian architects of the interwar period - and we can list here Gheorghe Simotta, Alexandru Zaharia, Horia Maicu, Nicolae Cucu, George Damian, Ion Giurgea, Victor Smighelschi or Octav Doicescu or Tiberiu Niga - practiced different styles during their careers, including what we call Mediterranean style. In parallel with neo-Romanian or Art Deco modernist works, constructions with an exotic appearance appear, rather at the request of the beneficiaries, which come from the directives of the Society of Architects, which vehemently supported the continuation of the national character in Romanian architecture. It is also the period of maximum leisure for Jewish creators, both avant-garde artists and architects - Alexandru Zaharia, Dori Galin Golingher, Grigore M. Hirsch, Corneliu Marcu, Horia Maicu, Leon Srulovici, Jean Krakauer, etc. Many of them with studies abroad, later equivalent in Romania. They will be able to create representative works in Mediterranean style such as; Elisabeta Royal Palace, Scroviștea Royal Palace, Adina Woroniecka House, Gh. Tattarescu House, etc.

The term Florentine-Mediterranean or, more simply, Mediterranean, is relatively unanimously accepted today, without sufficiently delving into the origin and influences of this short-lived stylistic moment, but with an important presence in the newly created Romanian urban space. It is remarcable that this type of architecture did not come into conflict with the urban site, integrating perfectly into the context, practically generating the future historically-protected areas, alongside neo-Romanian and other eclectic styles of the period. Architectural historiography has so far approached, with uncertainty, only the main currents, the guidelines of the period. Therefore, neither in the era, nor later, we do not find anywhere a coherent analysis of the eclectic-historical phenomenon, called Mediterranean. The few references written then and later, even have a strong defamatory character, considering this way of expression unworthy and unacceptable to follow in the mioritic lands.

In the Mediterranean concept, each house is created for a specific place, without being able to be replicated elsewhere. Many of the works made in this style were executed with Italian craftsmen, renowned in the interwar period, the final product being an exception, not a series. The attention to detail is an end in itself, the dozens of boards with beautifully drawn carpenters and ironsmiths will bear witness. The project itself is a work of art. Thus, at the level of concept and approach, we are dealing with modern thinking, which should be understood and practiced even today. The revitalization of local identity and the creation of that genius loci so sought after in contemporaneity, is the main merit of the Mediterranean historicist eclectic style.

Modernism will bring a paradigm shift, making repeatability and standardization a real cult, both from a strictly financial point of view, but especially from that of social uniformity, along the lines of socialist ideas and theories. The nonconformist American architect Lebbeus Woods claimed somewhere that all modernist architecture was based on socialist ideas. The ugliness of the city is given by the sordidness generated by the repetitiveness and programmed uniformity, and not by the plastic solutions of the straight line and cubist composition.

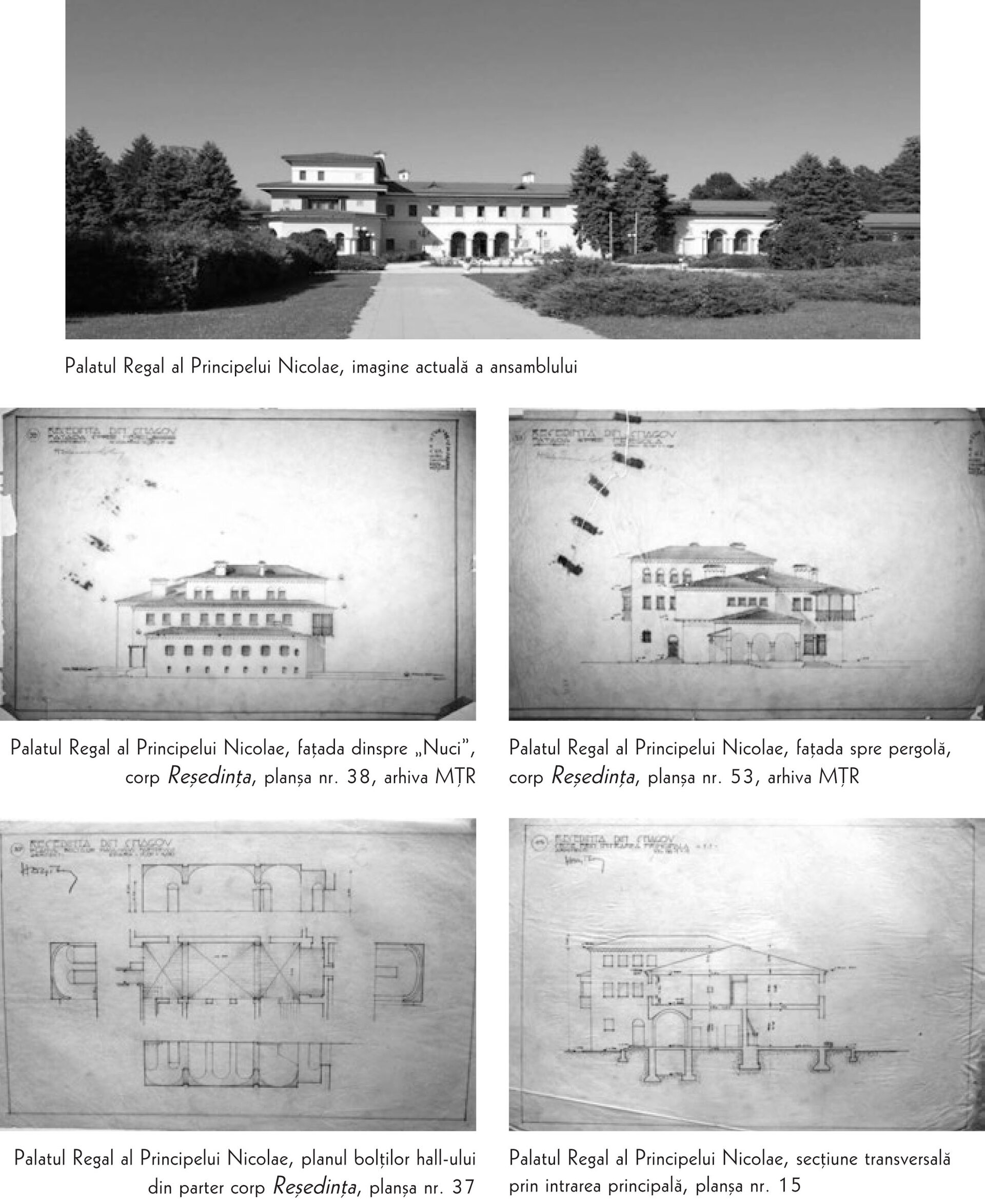

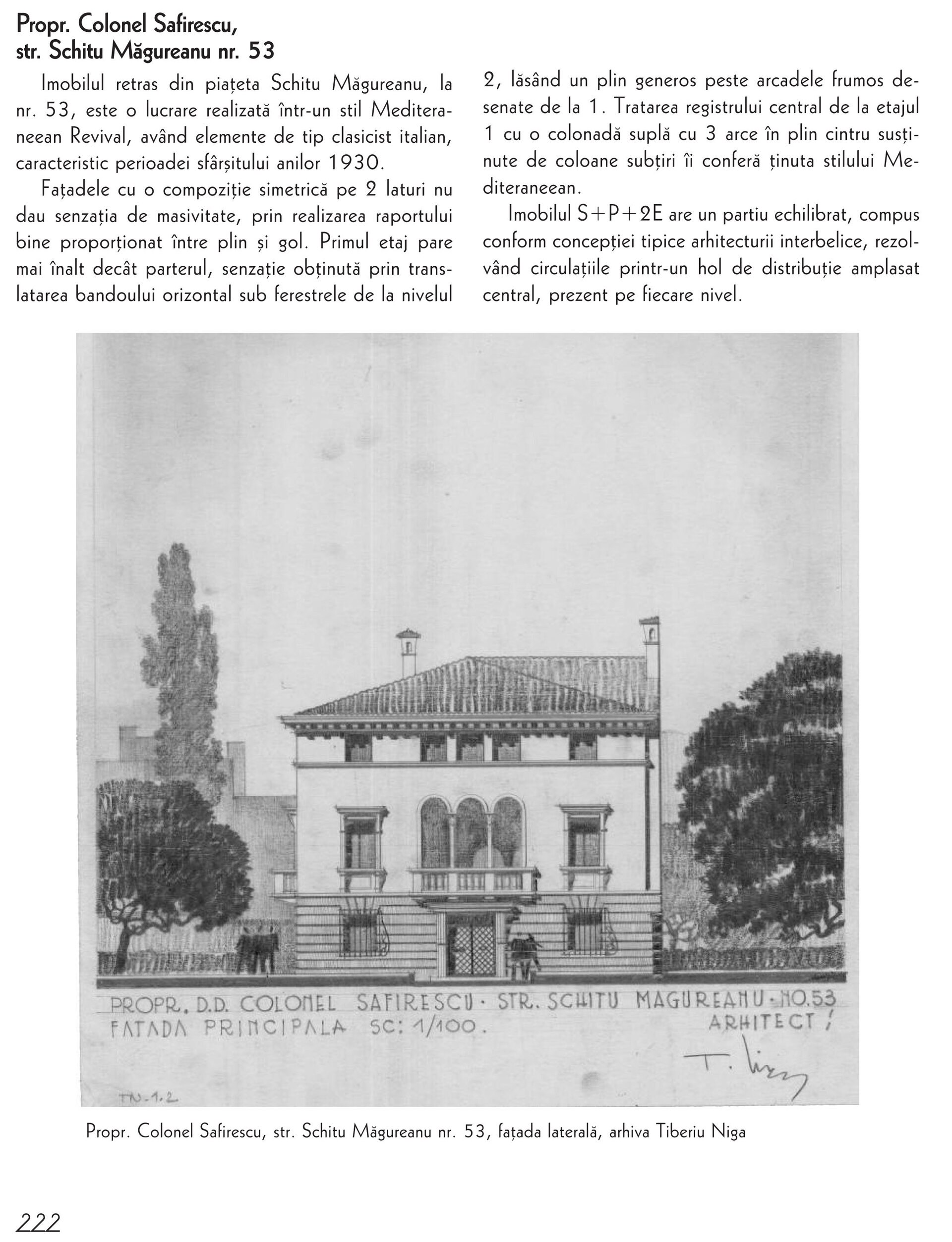

In conclusion, in the book, as a result of a Phd Thesis and an analytical and synthetic study, I presented the professional activity of 43 Romanian and 4 American architects as well as 500 buildings built in Bucharest and in the country ( mostly original works by author, previously unpublished ). By this, I argue that what is characterized by the 'Mediterranean Style' in the Romanian interwar architecture is a cultural phenomenon borrowed from the American realm, of a style that first manifested itself in the United States, with a preponderance in California and Florida at the beginning of XX century, until the 40s'. It had an echo and a strong representation in Romania, manifesting itself in two centers, primarily in Bucharest and Constanța, and with a few exceptions, in the province. To a large extent, the attachment of the architects to the Neo-Mudejar style that appeared in Spain at the end of the century is also evident. XIX, ( which manifests itself until the 1920s ). This eclectic-architectural moment from us is represented by major works, of great artistic value, which is represented by the residences of the Royal Family (Scroviştea Palace, Elisabeta Palace, Prince Nicolae-Snagov Palace, the 2 Villas of Princess Ileana, Villa Elena Lupescu), private villas of some personalities of the time (Gh. Tăttărescu Villa, Adinai Woroniecka Houses, Grigore Gafencu Villa, Veturiai Goga Villa, Minister Viorel Tilea Villa, etc.), but especially by the distinct presence of famous block-houses and villas in modernist-Mediterranean style ( Hagianoff building in St. George Vraca no. 7, etc.), which will contribute in a beneficial way to the urban aesthetics of the capital. Even more than that, although it is a phenomenon of borrowing, of taking over a fashion of the time, paradoxically, it will generate a unique character for Bucharest compared to the other Balkan capitals, where this phenomenon will not manifest itself.

The established stylistic terms of Florentine and Mauro-Mediterranean, or Mauro-Brancovenian, I believe that they should be reconsidered, studied alongside Mission, Spanish Colonial Revival, Mediterranean Revival or Neo Mudejar and Moorish Revival, distinguishing, however, that the Mediterranean Revival had the greatest influence, which included both Hispanic, Moorish, Gothic-Venetian and Renaissance-Italian elements.

Through the proposed work, an analytical study was carried out, in two parts, on several levels, first presenting the general Mediterranean context and then presenting examples from Romania.

A – Accessing various sources of documents, personal archives or state institutions;

- Archives of some architects - Tiberiu Niga, George Damian, Nicolae Cucu, Horia Maicu,

- C.N.S.A.S Archive – National Council for the Study of State Security Archives, through which important additions were made to the biographies of some architects, publishing for the first time several autobiographies signed holographically by the authors, as well as important references found in the tracking files located in this important source of study.

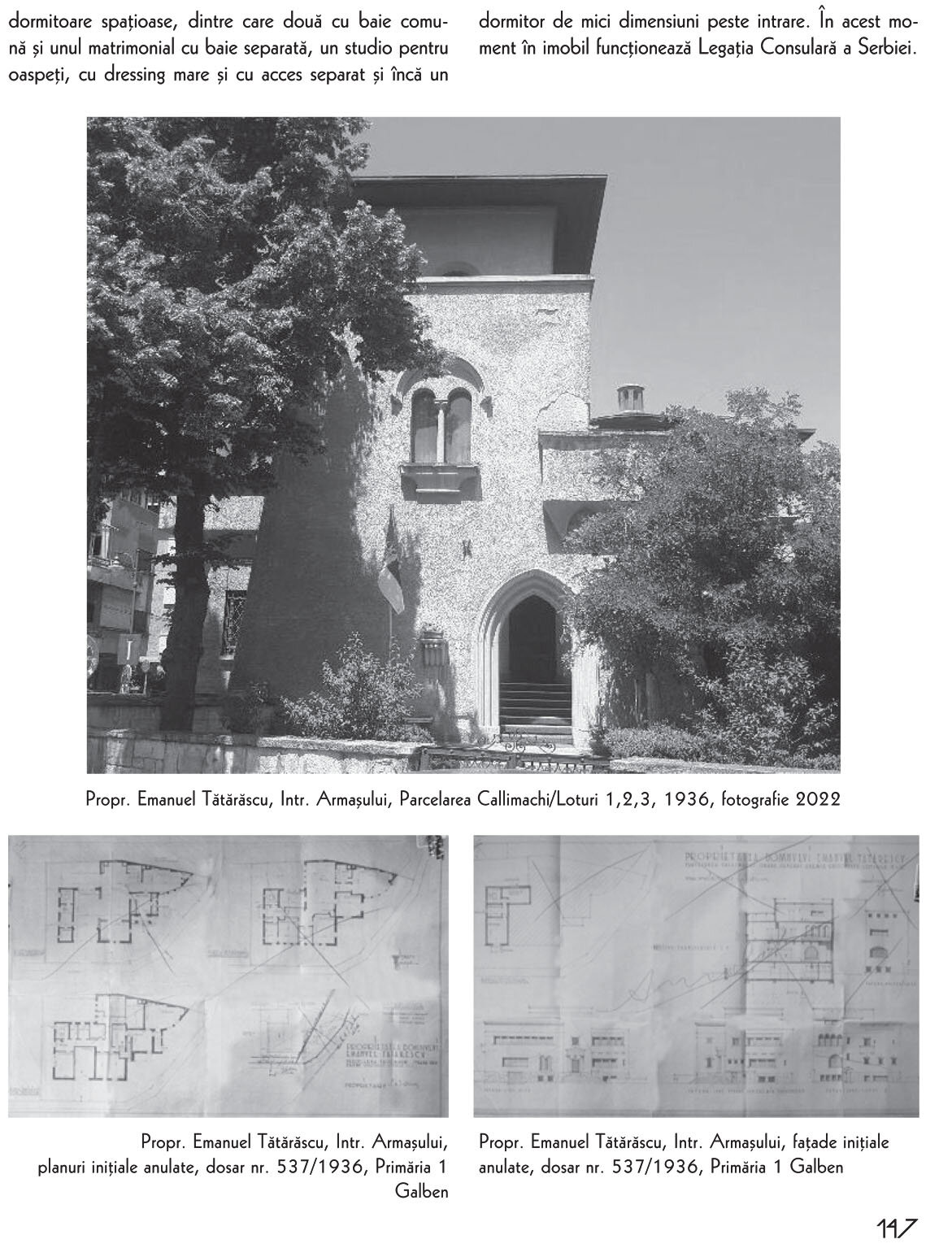

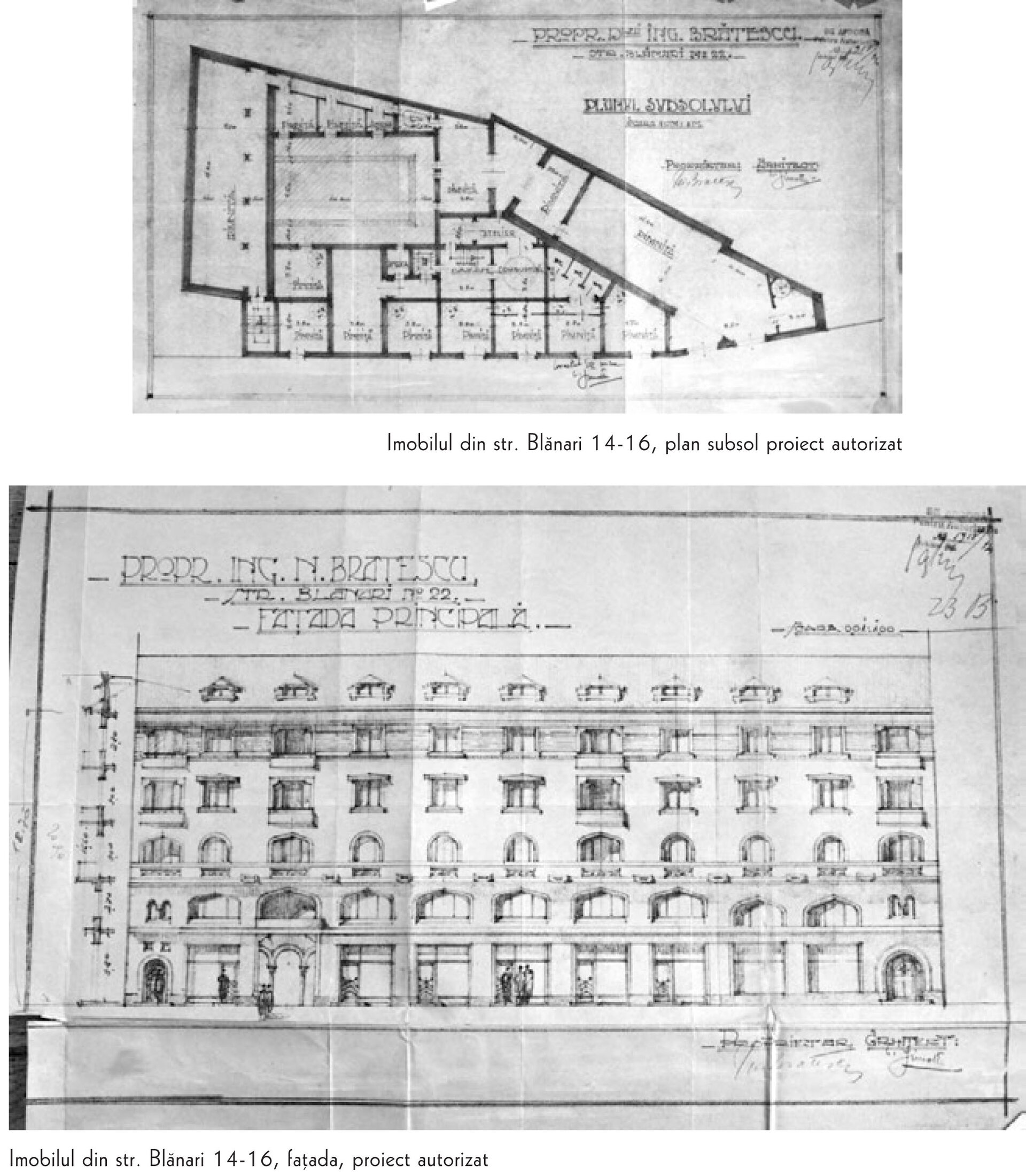

- P.M.B Archive – Bucharest City Hall, searching and photographing complete authorization files for no less than 130 buildings in Bucharest,

- Archives of the Romanian College of Architects, Fund of the College of Architects – personal files, National Archives, for brief biographical data of the architects.

- M.Ț.R Archive - Romanian Peasant Museum, where it was possible to photograph (through own technical resources), the archive of the project of the Scroviștea Royal Palace prop. Prince Nicolae, complex project of Henrieta Delavrancea, containing 497 drawn plates.

B - The presentation and publication for the first time of the theory of Prof. David Gebhard (1927-1996 - Professor at the University of Santa Barbara, California, member of the Society of Architectural Historians) who presents the evolution of the phenomenon in specialized articles such as: 'The Spanish Colonial Revival in Southern California' (1895-1930) published in May 1967 regarding the time studied in the American cultural space.

C- Argumentation of the theory of the emergence of the 'Mediterranean house fashion' in the Romanian cultural space, through the influence of the Californian houses, supported by the statements of the diplomat Matila Ghyka, published for the first time under the title - 'Escale de ma jeunesse si Hereux qui comme Ulysse..' - 1956, Publishing House La Colombe Paris, translated into Romanian - 'Rainbow' - 2014 - Polirom Publishing.

D – Presentation of the American context and 4 important American architects; George Washington Smith, Addison Mizner, Bertram Goodhue, and Wallace Neff, their biographies and portfolios.

E - The presentation and analysis of some written, unpublished, previously unstudied documents that refer to the Mediterranean phenomenon from the interwar period in Romania.

Jurgea Negrilești - 'Troica of memories' - Memoirs, 2 pages of references on the architect Al. Zechariah, text presented in full,

Mihail Manoilescu and sociologist Gheorghe Brânduș - article 'The Zukermann Style' - (about arch Al. Zaharia, articles published in 1941 and 1944), text presented in full,

George Călinescu – Roman Bietul Ioanide (various references to the style of Hispanic-Gothic houses),

G.M. Cantacuzino - article 'Mitocanul in Romanian culture', Simetria Magazine (references to houses with Mexican facades),

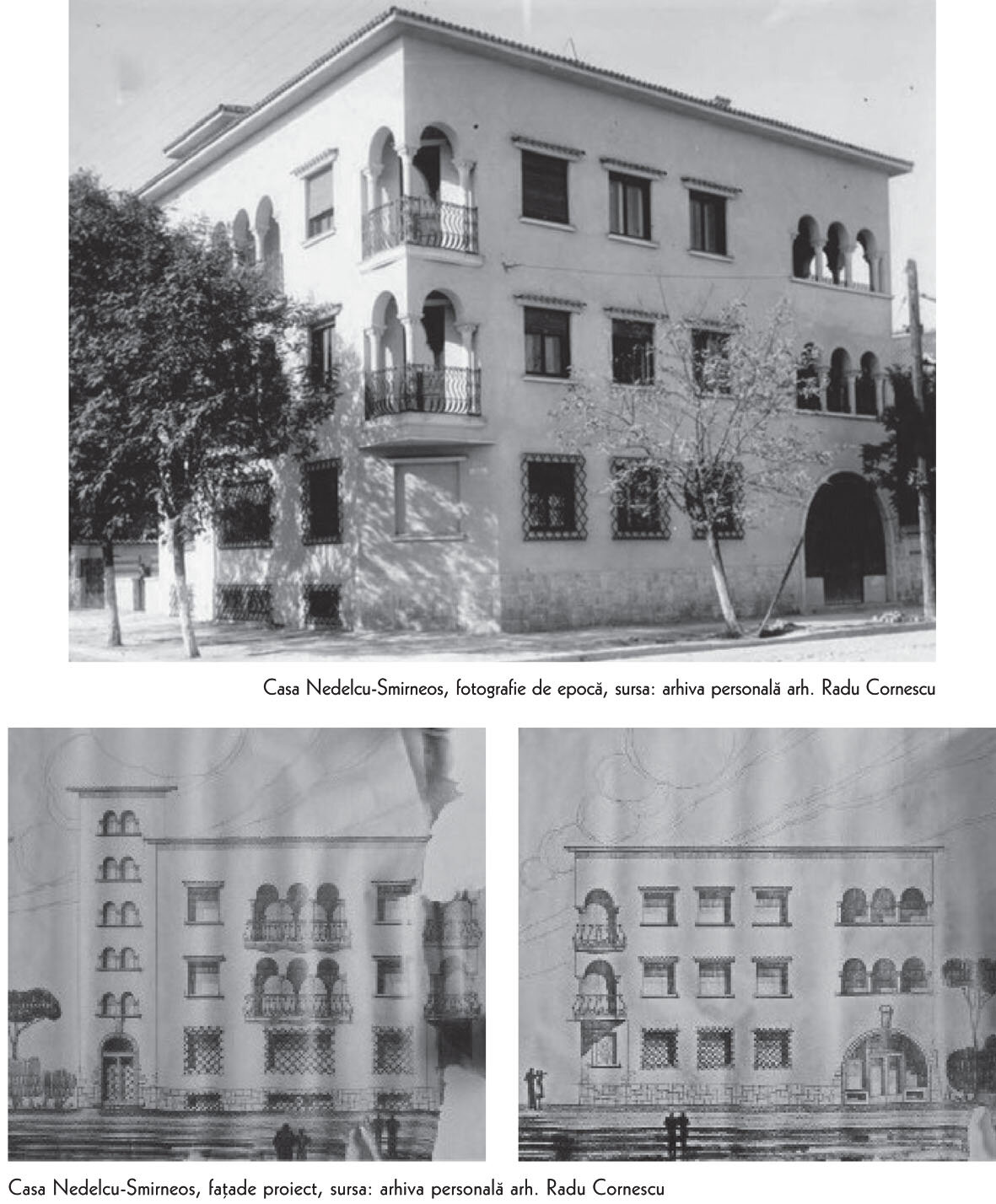

F – Realization of a classification of buildings made in the Romanian cultural space, distinguishing 3 typologies of the design of facades and interior and exterior decorations;

- 1 building with Hispanic and Gothic-Venetian influences,

- 2 buildings with Renaissance-Italian influences, purged of Gothic decorations,

- 3 buildings made through the local synthesis created by the architect Octav Doicescu, by adapting-transforming a general Renaissance-Italian concept, by inserting neo-Romanian elements, which can be called an 'Octav Doicescu Style'.

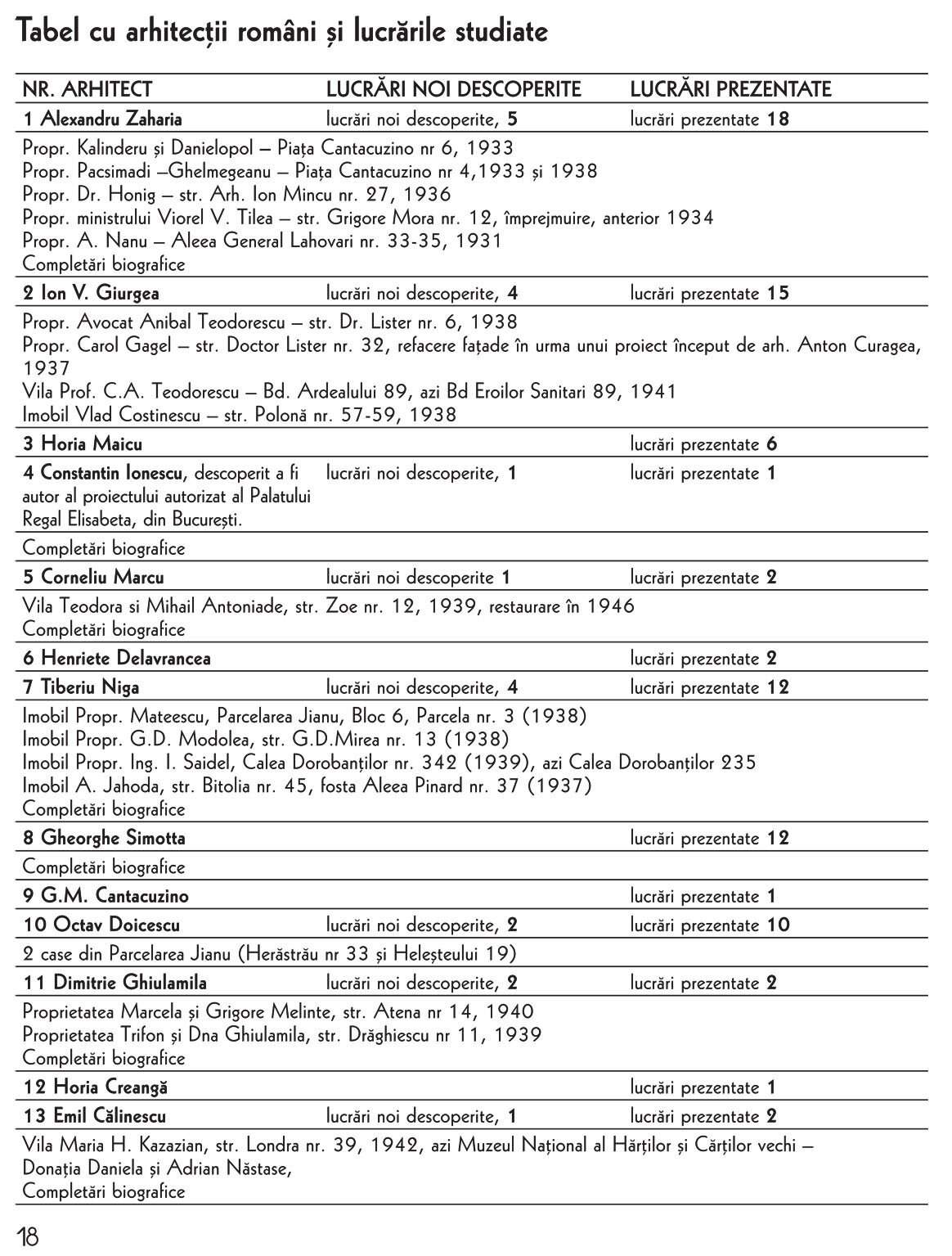

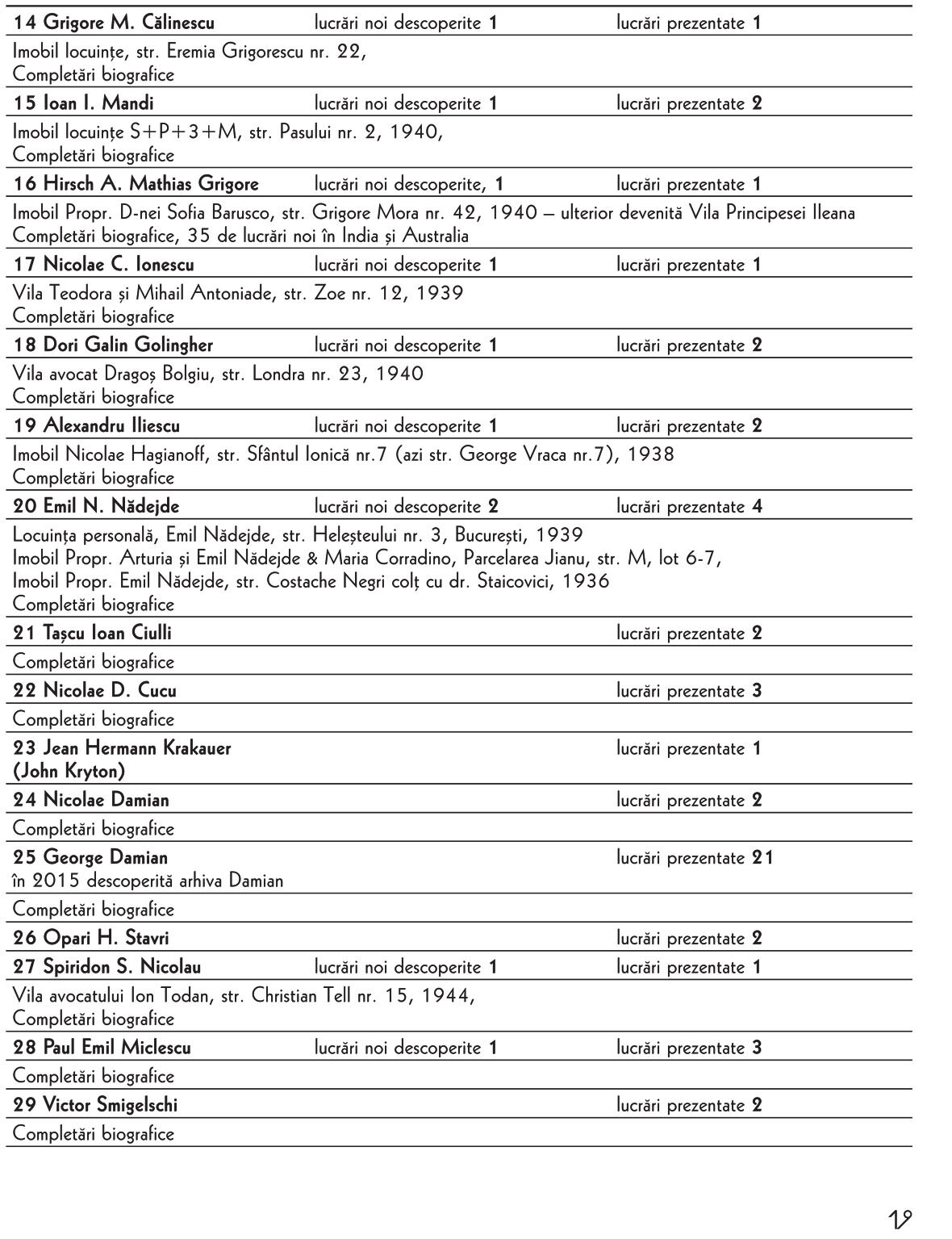

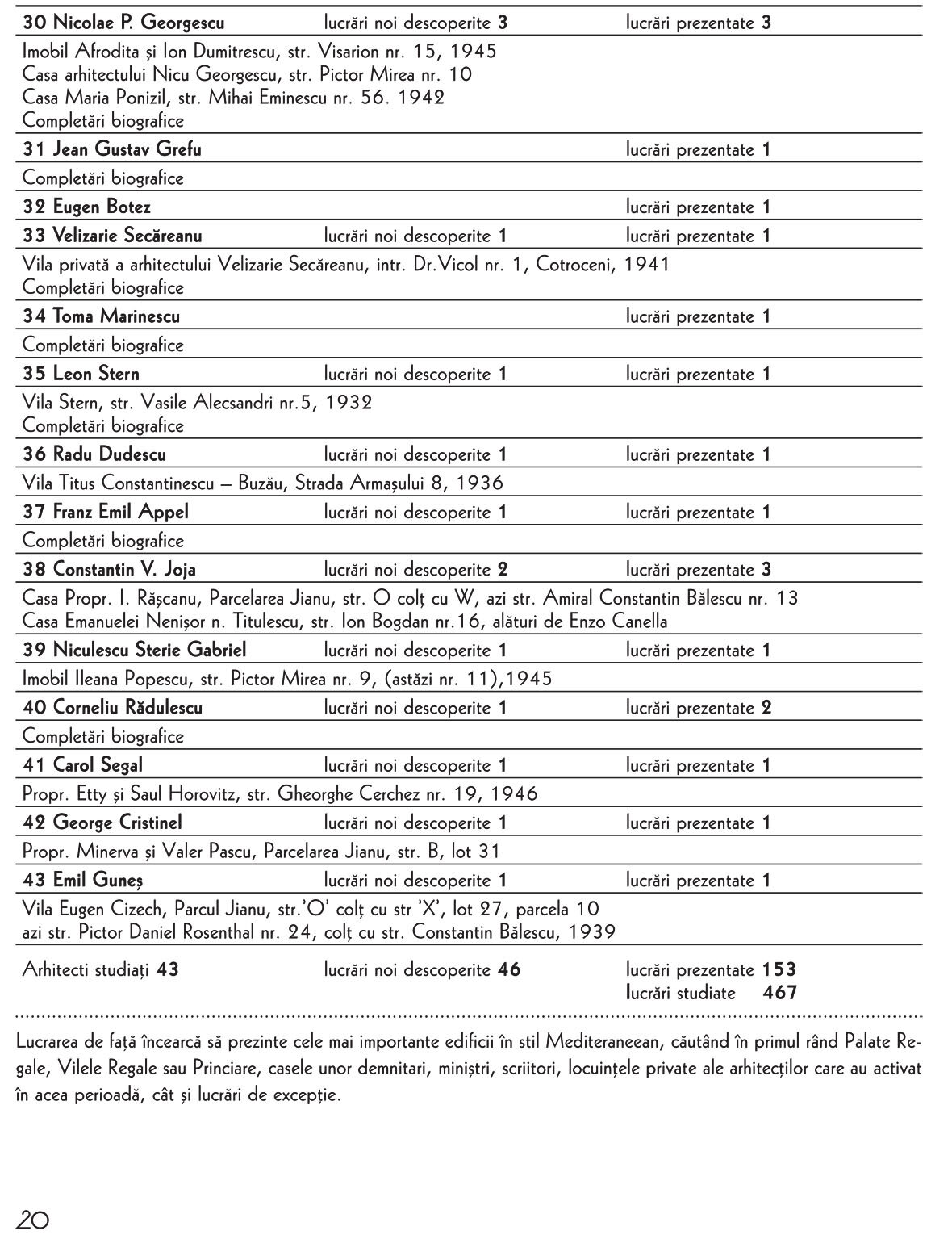

G – Presentation of the biography and portfolios of 43 Romanian architects, analyzing the works with a Mediterranean aspect. 46 newly discovered works are highlighted out of 153 presented and 500 studied, both from Bucharest and from the country.

- The Rehabilitation of Built Heritage. Theory and Technique

- Goldstein Maicu. Modern Villas.Constanța. 1931–1940

- The mediterranean architecture in romanian interwar period

- The Academic Community of the Architecture University

- Digital modeling of the impact of the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake / Second revised edition

- The Impalpable in Architecture. The Oikological Vocation and the Cosmotopic Character of the Architectural Interior

- The Dynamics of the Christian Lithurgical Space. The Influence of Function - 2nd edition revised, completed and actualized

- The Arad citadel. Architectural valences of the relationship between history and city

- Set Apart. Evangelical Worship Space

- Proportions in Architecture. Perceptions and spatial identity.