Villa Suburbana

Authors’ Comment

Villa Suburbana is a house that emerges from the generic conditions of Bucharest's periphery.

The project raises questions about generics, cultural adequacy, typologies, and the relevancy of our profession to the middle-class – represented by independent and pragmatic people, with cultural and aesthetic references that need to be understood by academia before criticized.

The periphery of Bucharest is often chaotic, densely occupied, dysfunctional, anonymous, and lacking proper infrastructure. Nevertheless, it’s growing with people who come here for the privacy of an individual house and for their own back yard. This was also the case of my client.

The project started as a hilarious design brief and developed into an ongoing research. Initially, the client, an engineer, came with the plans of a catalog house that he liked and asked for help to change the type of stairs. During some long discussions, he mentioned a few other conditions that would make his house very different than the one he saw in the catalog (the number of bedrooms and the fact that he doesn't want an attic), so in the end, the brief focused on how to transform that into the client's future house and on identifying what exactly he liked about it, in order to embed any existing qualities in the proposal. Another important factor was the lack of a site. He didn't have land, but he knew the rough area where he would buy, how large it should be (500 sqm), and that it will be a flat terrain.

In school, we are taught how to work in a particular context. How do you work in a generic context that is barely urban and doesn't seem to have qualities?

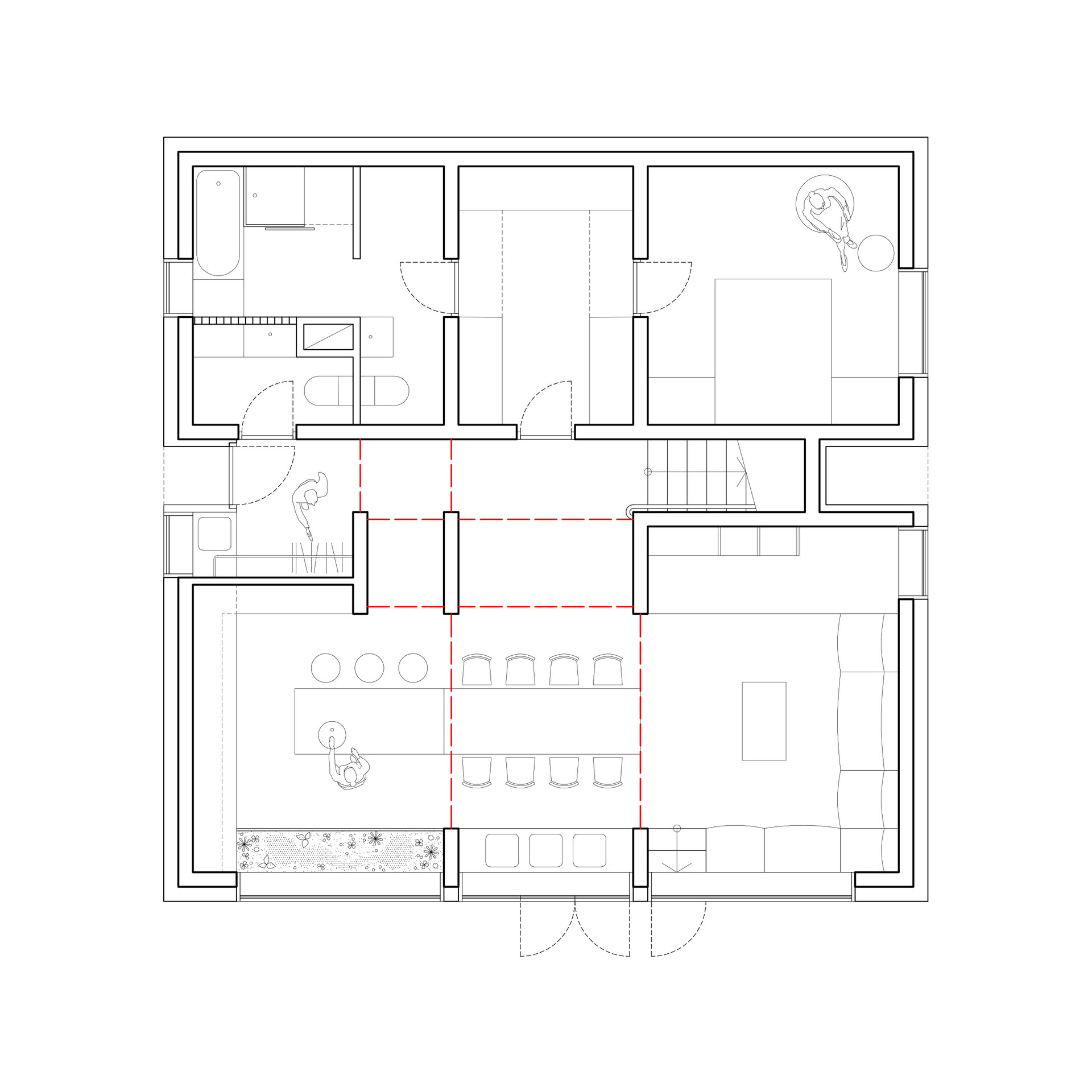

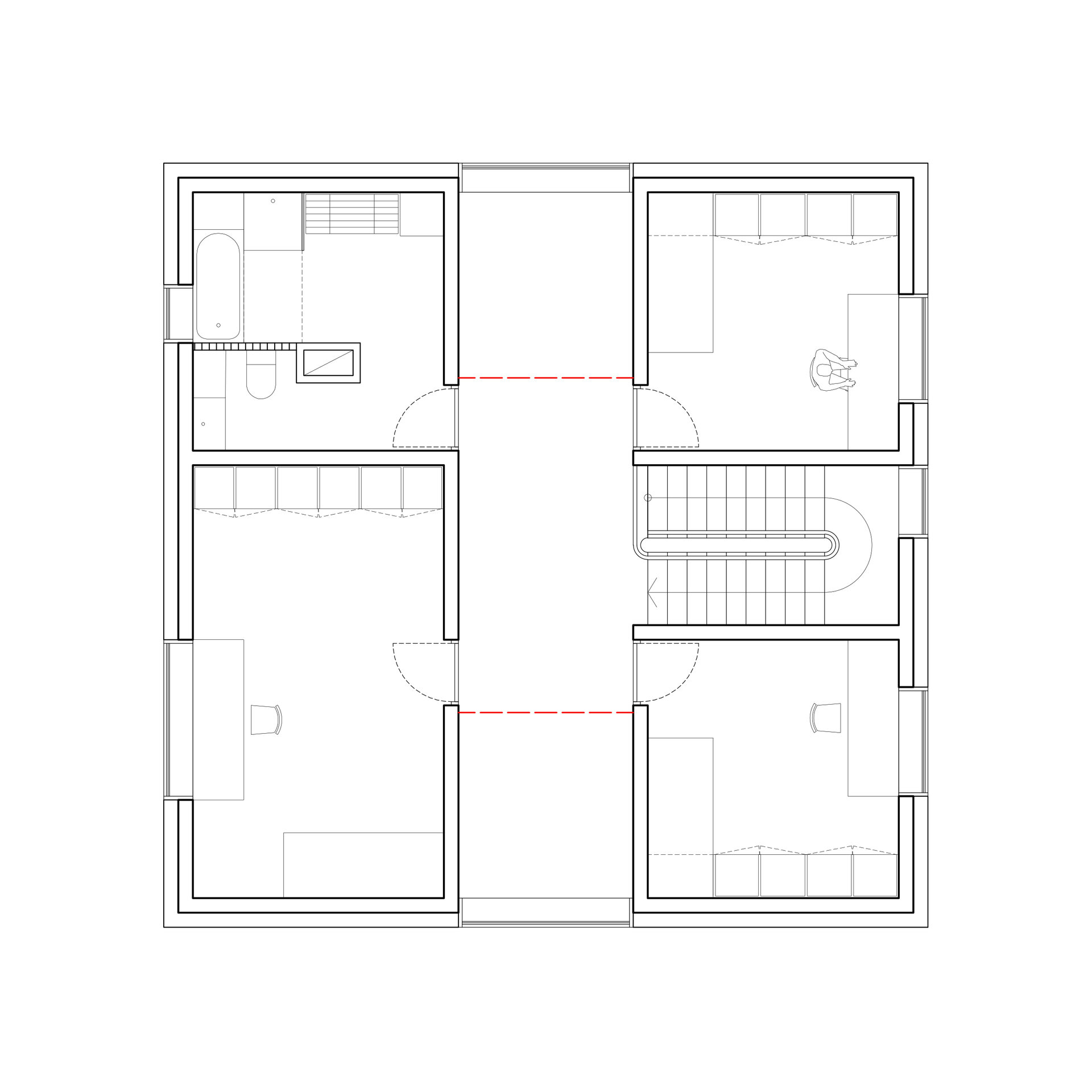

The key of this project was to accept these strange conditions as challenges and to work with them. The project strives to include the most personal ambitions of the client: a cozy reading room under the stair; four bedrooms positioned very precisely – the master bedroom on the ground floor and the children's bedrooms on the first floor; a generous kitchen and a dining space for the numerous dinners with the extended family; last but not least, a terrace oriented towards the future garden.

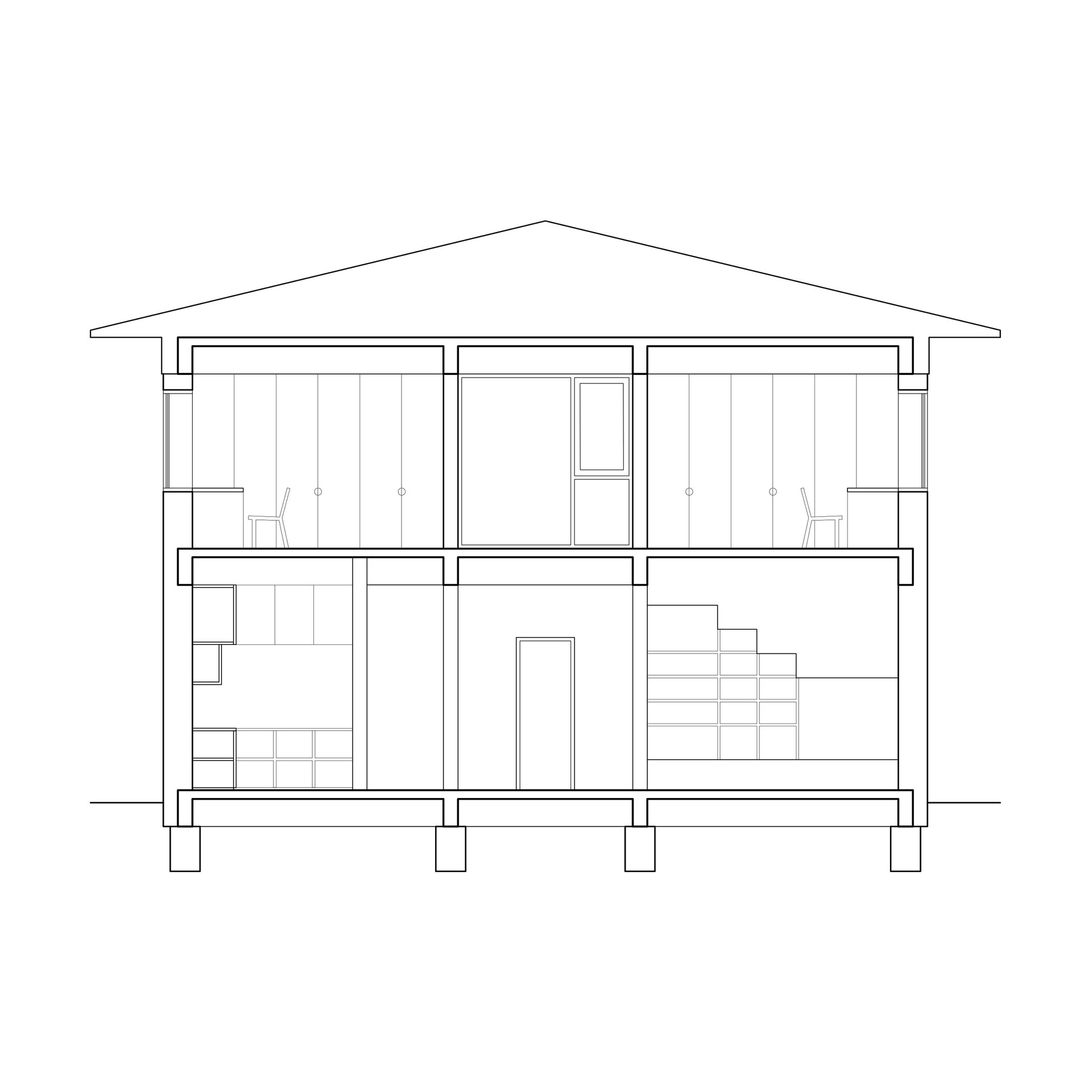

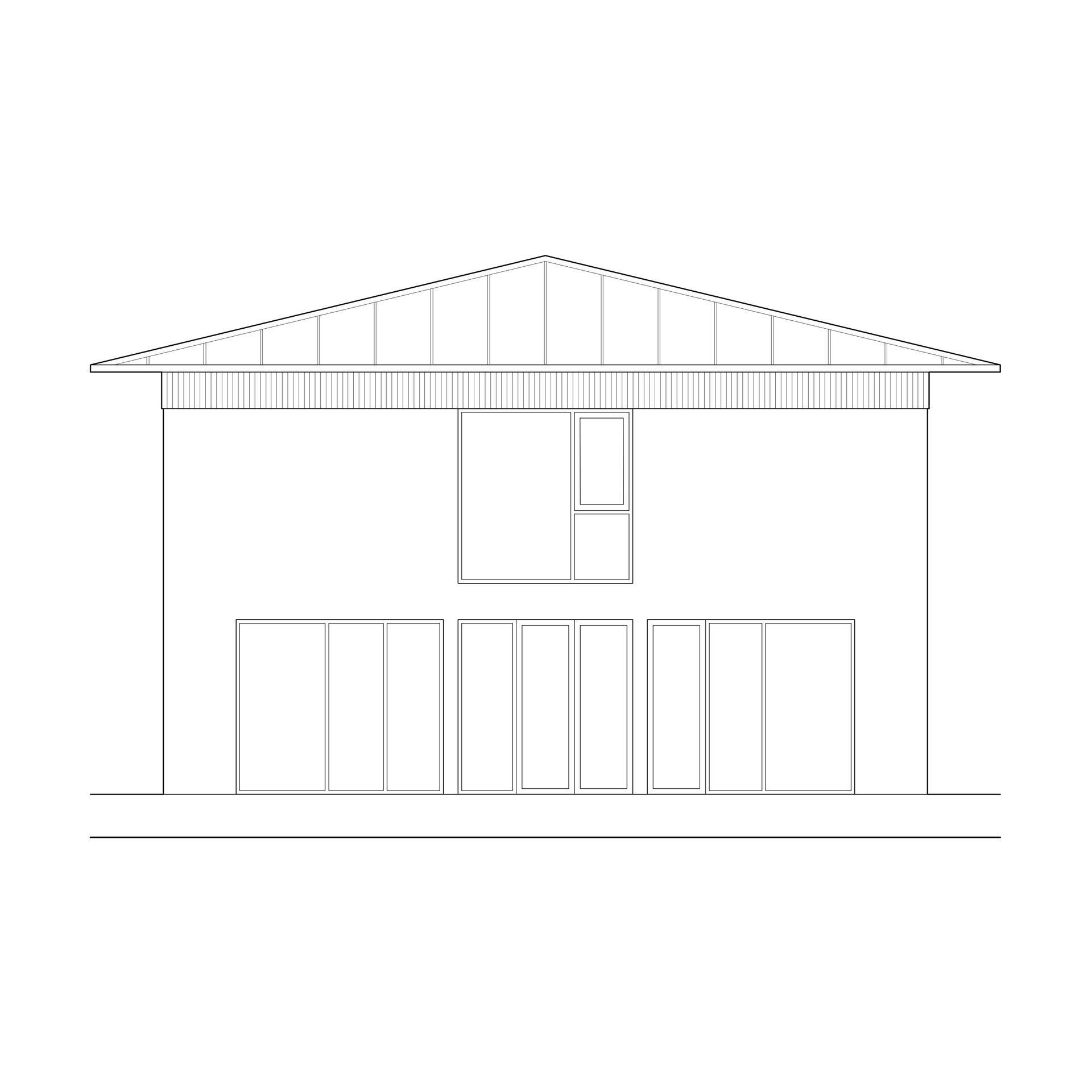

In addition, since there is no valuable context to refer to, the house only responds to essential factors, such as optimal natural lighting, cardinal orientation, the relationship with its garden, spatial efficiency, adaptability in time, and economy.

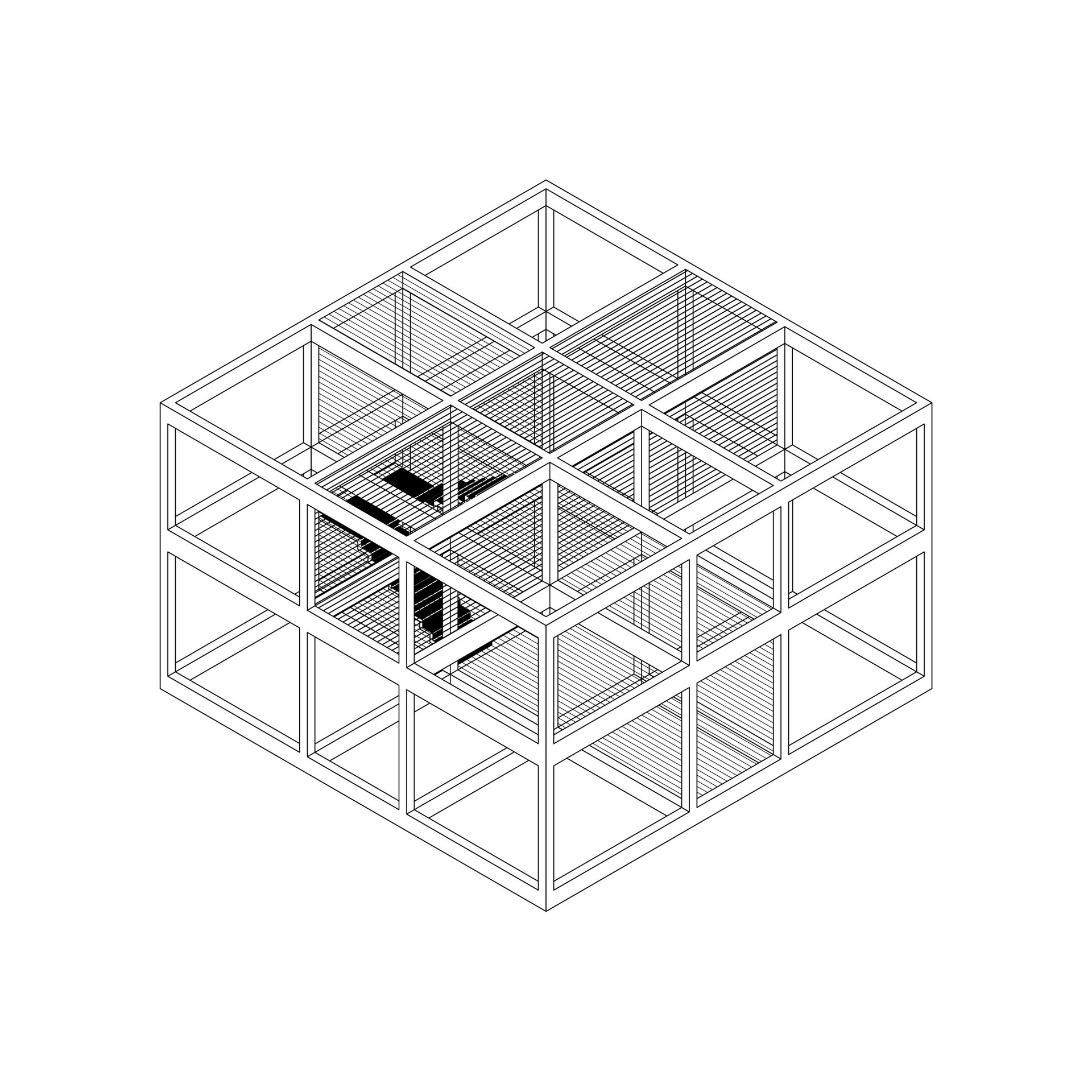

The symmetry establishes a neutral relation with any potential neighbors. The simple structure divided into 9 cells allows for an efficient partitioning. The distribution spaces of the ground floor and the first floor are perpendicular, so all the rooms receive optimal lighting.

This flexible overall frame, which allows extra space division, empowers the user to respond independently to any changes in his life (anticipated or not) in a controlled way that would not affect the architectural integrity of the house in the future. In other words, the house was conceived not as a building, but as a system that foresees a variety of scenarios and can easily adapt to any of them.

The goal of this project is not as high as changing the periphery conditions, but rather to accept chaos as a given and learn how to work within it. The area seems to have a metabolism of its own, but we need to acknowledge that it’s part of the city.

If we take it seriously, we will gradually educate ourselves and the users and change these conditions from the inside, but this can only happen in time.

- MA House

- House in the forest

- Collective dwellings – 13 Septembrie

- House on Scroviștea Alley

- Commuters’ Village

- House MC

- Cihoschi Housing

- Estera Residence

- Dumbrava Vlasiei Passive House

- ICABU Housing

- Deck House

- Cc House – Modular Concrete Housing

- I.RD House

- House by the lake

- House in the mountains

- House with a garden

- House with a library

- House with a tree

- Shape Towers

- Lines Tower

- Carol Park Residence

- Lagoon City

- Suburban Retreat

- Snagov Retreat

- Villa Suburbana

- F8 House

- ELEV8 Residence

- House with a view

- Urban Development in the Northern Part of Bucharest

- Urban house

- Single unit housing

- The Pool

- Countryside house

- P62 House

- The Sun House